Elected ARSA: 21 March 1956

Elected RSA: 8 February 1967

Esme Gordon,R.S.A., F.R.1.B.A., F.R.I.A.S. (1910-1993) A posthumous portrait.

“The Annual Reports, with the passing of most, but not all, being noted, record milestones in lives devoted to Art. Regardless of date, these valuable statements of professional life and achievement have in common one endearing characteristic: artist friends in affection salute, a departed friend, a fellow craftsman. In themselves these obituaries are also a review of change: change in taste, change in esteem and change in attitudes to Death. We see the men not in terms of the reputations they have today, but as their contemporaries wished them to be seen” (E.G.)

I first met Esme intheearly1950sat Edinburgh College of Art, in the era when, as part of a two-year General Course, potential specialists in the fields of painting, design and sculpture were required to study ‘Architectural Drawing’ as part of the curriculum. I confess to being at one with those in an unruly and reluctant rabble of art students who viewed the prospect of this subject as an irrelevance — A preconception made in youthful arrogance which was to be confounded by experiencing the good fortune of coming under Esme Gordon’s tutelage. |joined a legion of students with whom Esme established a rapport, indebted to both his humanity and wisdom.

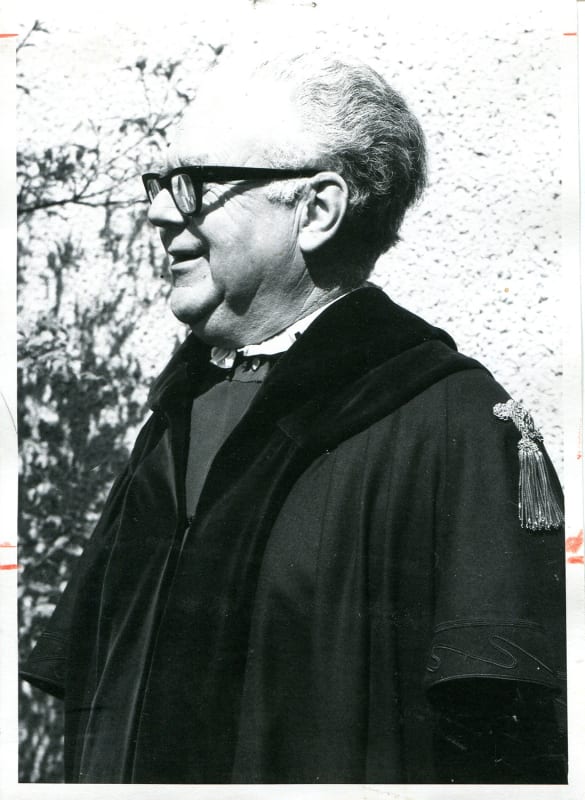

Subsequent acquaintance which was to grow into friendship still leaves the first impression basically unalloyed. Of medium height Esme was a portly yet elegant figure; whose hair in a transition to eventual whiteness was salt and pepper brindled, wiry and wavy, was swept back with a strong growth above his ears.

Immaculately tailored in a dark suit, he sported a favourite mustard waistcoat and a bow-tie of a pattern which varied as his fancy dictated. This was a garb which served not so much as a demonstration of his discriminating taste as to advertise membership of his architectural profession, for in those days (paralleling the insect world) there was a general obeisance to not too subtle dress- codes, where one had to be particularly insensitive not to recognise such signals of recognition. Yet, while sartorially Esme could be described as the epitome of an architect, the salient impression was that of his personality: an avuncular presence where thick-framed spectacles were but windows to the eyes which conveyed warmth, curiosity and more than a hint of Puckish humour.

From such beginnings, my appreciation of the rich and complex nature of Esme’s personality was to be continually punctuated by surprise. In our all too infrequent meetings at a sociable level, |came to know the private man whose sense of humour could be a slight as a souffle, or school boyishly, disconcertingly earthy.

Though Esme could be genuinely distressed by folly, this was counterbalanced by the acuity of observation which marked his delight in the comedy of life’s Vanity Fair, oft encompassed in an apt and pithy comment remaining unbarbed by either the malice of acerbity which so often passes for wit.

Such humour was in contrast to the seriousness of Esme’s public persona, but

Only a seeming contradiction. By nature scrupulous and exacting in his standards, his fellow Members’ knowledge of Esme’s probity would engender keen anticipation rather than apprehension at meetings where his sense of duty demanded that he should make a public announcement. With a mein appropriate to a most genial and charitable elder of the Kirk, Nis deliberations would be rendered with a measured and urbane style. More often than not an historical anecdote germane to the point he wished to make would preface his comments. Esme would prompt rather than negatively criticise, proposing better alternatives, and so transparent was the benignity of his intentions there was never cause to take offence. Even so, it would be idle to pretend that such deliveries were to everyone's taste -Esme, bless him, knew how to prick a conscience (never a comfortable experience) and in his desire for gravitas he could sometimes provoke impatience.

In private moments, this stalwart champion of the Academy's welfare, at war with the politics of expediency would debate with me matters of mutual concern. How Esme voted in a broader political context must remain a secret of the ballot-box. Of one thing I am certain, Esme was not only an individualist but also an idealist who would resonate to the best of any political manifesto only So much as It was in accord with his staunch Presbyterian convictions.

In such a perception I would not wish to be misunderstood; Esme was no censorious Calvinist, for remember well discovering that I shared with him an unabashed pleasure in the frank sexuality expressed in Indian Sculpture, which he accepted as a natural part of the human condition. While I would not wish to over-stress this hedonistic streak in Esme’s character, nevertheless he was without doubt a man of epicure an judgment, relishing all things of quality, and finding a primary source of spiritual nourishment in a past from which had been filtered enduring values. Thus, classical music counted amongst many joys which enriched his life, the love of which he shared with his beloved wife and help-mate Betsy who had been trained as a concert pianist.

Though Esme’s artistic tastes were catholic, he cherished a particular enthusiasm for Oriental Art. This was, I suspect, because he was psychologically attracted to an art with a philosophy which whole-heartedly embraced a tradition spanning millenniums rather than decades, holding in reverence any individual contribution which, while maintaining a respect for precedents, advanced the tradition and added to the general wealth.

Esme’s enchanting Edinburgh home at 10a Greenhill Park (which sadly he was later in life to abandon, in despair at the befoulment of burglary) proclaimed his impish delight in confounding by surprise. As an introductory symbol of this trait, the front garden vaunted a solitary and Imposing lonic column, and on entering the interior of the house, one was no less astonished to find a choice mixture of inherited art, contemporary Scottish paintings and oriental art which in being hung and arranged to produce unexpected conjunctions, conveyed something of the potent interactive vibrations found in the Japanese Poetry of the Haikuorin Presidency of the Edinburgh Architectural ‘Metaphysical Art’.

This was no mere dilettante display, for Esme the collector combined personal response with an enthusiasm to explore in depth by research and travel. Thus it was that as a connoisseur of Chinese Jade, Esme melded a passion with authority in a swan-song public lecture Organised by the Friends of the R.S.A.in 1992.

Surprise also provides the link between personal reminiscence and factual biography. In an awareness of his brilliance as a raconteur, it would be natural to expect that the R.S.A.’s biographical file would be replete with anecdotal and autobiographical revelations. Not so. Certainly, it contains a letter to the President W.O. Hutchison expressing gratification on his election as an Associate which he concludes with a vow of loyalty which is entirely characteristic.

And in a press cutting from ‘Scotland on Sunday’ after being approached by a journalist with the question “which three things would you take with you if you had to flee Hurricane Andrew?” he responded with an unerring eye for quality. ‘We haven't got a cat so I would take D.Y. Cameron's ‘Interior of Durham Cathedral’—it’s a damn good painting, beautifully composed, and really almost an abstract. I’d also take William Etty’s copy of Titian’s ‘Venus of Urbino’; the original was Titian at his best and the copy is better than the original; and Thomas Hamilton’s 1850 designs for the Academy which were never used’.

However, as Esme was someone whose focus constantly lay beyond himself, neither I nor anyone else acquainted with Esme's personality should be too astonished that his R.S.A. biographical folder yields little beyond the aforementioned — the gleaner finding a Field already winnowed.

Though meticulously, Esme provided a hand-written curriculum vitae, this is pared down to the barest of essentials; indeed it is so filleted that it reads as a condensed summary often found at the end of a newspaper obituary. Such genuine modesty revealing a lack of egotism must be seen as typical. Significantly, only in the Introduction and Acknowledgments of his book on the R.S.A. did Esme feel obliged to employ personal pronouns. His philosophy and character are beautifully expressed in the opening paragraph of this acknowledgement: ‘Should not first words of gratitude be to express thanks for the gift we share of vision?'

Were it not for our appreciation of form, of colour and of those many skills with which the mind, guiding the hand of Man as it strives, maybe unconsciously, to express the deep things that matter, life would be artless, impoverished— and, incidentally (a minor consequence), the pages which follow would by me, a mere Onlooker, have remained unwritten.’

In fleshing out the over-concise and all too skeletal biographical details which Esme left us, am particularly indebted to the tribute by Sir Anthony Wheeler and Robert Scott Morton published in ‘The Independent’.

Alexander Esme Gordon was born on 12th September, 1910, the son of a solicitor, and like Robert Louis Stevenson, he was brought up in the elegant New Town terrace of Heriot Row. (It would seem that Esme’s father was a man of percipience: he was to commission a young Orcadian artist to paint Esme at the age of five in a sailor suit. The artist was Stanley Cursiter later to become the Queen’s Limner in Scotland and a distinguished predecessor of Esme as Honorary Secretary).

After schooling at Edinburgh Academy Esme embarked upon a six-year architectural training in the School of Architecture at Edinburgh College of Art, a studentship which included practise experience in the London offices of Sir John Burnet, Tait and Lorne.

He was quickly to make his mark, and in his qualifying year at the age of 24 his artistic bent was recognised when he won the RIBA Owen Jones Scholarship for his knowledge and skill in the field of colour. Two years later in 1936 he set up practice in Edinburgh and became closely involved in design work for the 19383 Empire Exhibition in Glasgow. At the start of the Second World War Esme designed and organised the building of canteens for the troops, from ‘Shetland to the Bay of Biscay’, before being called up for active service in the Royal Engineers.

After war service he returned to his Edinburgh practice, and his commissions (mainly Edinburgh) included work for Heriot Watt, the head office of Scottish Life in St Andrew Square, the George Street head office and showroom for the then South of Scotland Electricity Board, as well as the design of several new churches elsewhere in Scotland.

Recognition of his sterling qualities was acknowledged by Esme being elected to the Presidency of the Edinburgh Architectural Association in 1955, and in the middle of his two year period of office in 1956 he was elected an Associate of the Royal Scottish Academy. He also was appointed to be a member of the Scottish Committee of the Arts Council serving from 1959 to 1965. In addition he served on the Councils of the Royal Institute of British Architects and the Royal Incorporation of Architects in Scotland. He was elected a full member of the R.S.A. in 1967.

William Pirnie, now a senior lecturer in the School of Architecture at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art in Dundee has spoken to me of his affectionate memories of Esme. In the mid-decade of the sixties as part of a ‘sandwich course’ Bill served an apprenticeship in offices of Gordon and Dey in a period when Esme was designing Dr Guthrie’s Girls School at Gilmerton. Bill marvelled at Esme’s skills as a draughtsman, when without aid of either tee-square or ruler Esme could draw the straightest of lines perfectly to scale. Esme’s office was truly more of a ‘studio’, designed with an eye to practicability -hence it housed a well-stocked library, and (though I am writing of the Sixties) a ‘mobile’ telephone.

This last was a trolley, the carriage to a telephone with an extension lead long enough to ensure that wherever Esme’s perambulations with in the office took him, the telephone would always be easily to hand.

With Esme’s profound belief in the value of observation, on one occasion Bill was to find himself severely challenged: (In the following dialogue in period Esme preserves the formality of addressing by surname alone).

EG ‘Pirnie, am I correct in thinking that every day you walk to the office via Lothian Road?’

WP ‘Yes sir’

EG ‘Then tell me Pirnie, the number of windows on the facade of Binns’ store’.

The above is but one example of Esme’s astuteness in keeping a student on his mettle, which Bill Pirnie treasures training’. He revered Esme as ‘a marvellous not only as a human being and teacher, but also, without cynicism spontaneously described him as ‘the last of the great Edwardian architects’. In a ‘post-modernist’ age we may recognise such a judgement as apposite; the robust individuality of Esme’s architecture being more easily equated or associated with, say, that of the no longer derided Lutyen’s, in preference to more technologically inspired 20th century architect heroes.

Nor can be ignored Esme’s genious as an architectural restorer. Not since Sir Robert Lorimer has a Scottish architect been so sensitively attuned to history, and such special talents were unobtrusively employed in Edinburgh’s St Giles Cathedral, the historic Canongate Kirk, and St Andrew’s Church in George Street. No-one can cavil with the obituarist who wrote in ‘The Scotsman’ that ‘much of the meticulous and skilled interior work which he carried out as an architect for St Giles Cathedral he regarded as a Christian duty, for which some believe he received less credit than he deserved’.

Esme has also a published study of the High Kirk of St Giles, as well as a work on church building. To describe Esme as an artiste mangue, would be inappropriate for he was a creator who found art and architecture to be one within an indivisible family. Our architect cum artist’s drawings and watercolours were more often than not topographical, and often contained human figures. Esme’s appreciation of the distilled quality which distinguishes somuch of Eastern art was reflected in works where precision happily combined with delicacy.

As Esme was himself punctilious in observing the Academy’s Constitution and bye-laws (one suspects a legal mind inherited from his father) woe-betide any fellow-Member who was foolish enough to imagine that these were inconveniences which could be subverted by submitting work under the umbrella of a member's label to be exhibited in a discipline other than that to which the member had been elected. Correctly, Esme insisted that ‘subject to selection and on merit’ was the rule of the day, and thus it was quite properly Esme’s far more than competent watercolours would grace the walls in many an Annual Exhibition.

Beyond such regular representation at the R.S.A., one must make note of an exhibition of fifty-two works in the Scottish Gallery in 1988. This was a showing which he shared with another distinguished Academician, the painter Denis Peploe, a public association which reflected friendship.

In the obituary on Esme published in ‘The Independent’, Sir Anthony Wheeler rightly ranked the seventeenth Hon. Secretary of the R.S.A. (1973-78) as ‘one of the greatest’ and further proclaimed” Gordon's incalculable contribution to the affairs of the Academy’. In such a context Esme’s published history of the Royal Scottish Academy commands special mention (See Librarian’s Report) but neither demittal of office, nor retirement, saw any diminution in Esme’s desire to be of constant service, a devotion which was only to cease with his passing.

Esme has left both the R.S.A. and Scotland at large many monuments of practical achievement. So truly does the style reflect the man, that his choice of words for the Academy's motto ‘Dignity and Force’ will endure as a fitting epitaph.

Yet, for many, the abiding memory of Esme Gordon will be that of a charitable spirit which will continue to illuminate our lives long after his death. Thus I conclude with words written to me by one of his closest friends in days of shared grieving and the pain of loss ...‘Esme was a joy’.

RSA Obituary by Peter Collins R.S.A, transcribed from the 1993 RSA Annual Report