Elected ARSA: 21 June 1989

Elected RSA: 25 February 2005

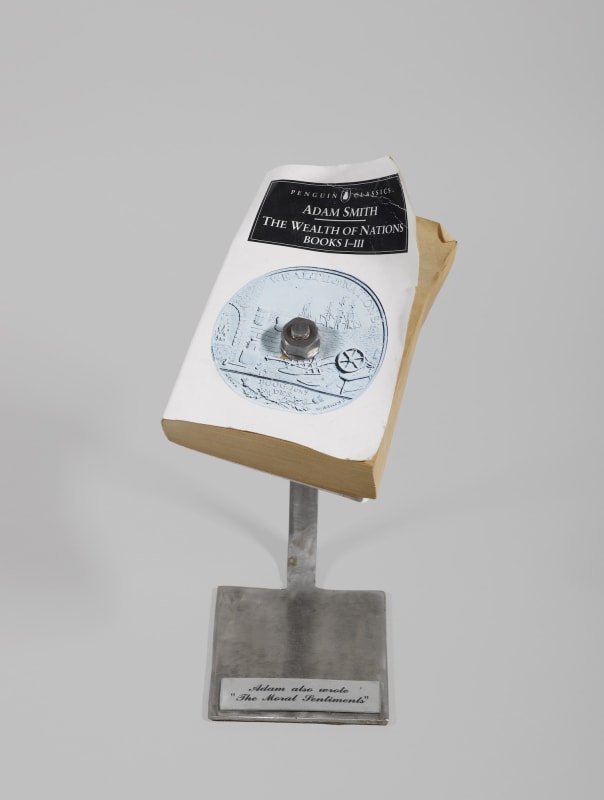

George Wylie RSA was born on the 31st of December 1921 to parents Andy and Harriet Wylie. Wylie received no formal art education but was taught by his mother to play the ukelele, draw, paint and dance from a young age. He went on to work several jobs before emerging in the art scene including designing manholes in the Post Office’s engineering department and serving in the Royal Navy during the Second World War.

In 1965, Wylie decided that “It was time for art”. He set himself the goal of creating 10 objects. He ended his project with a crucifix which was accepted by the Royal Scottish Academy and was later purchased to be displayed in a church in Barrow-in-Furness. He left his job in the customs service in 1979, aged 58, and began his four-decade career as an artist and sculptor.

Wylie’s most notable work includes the Straw Locomotive (1987) which hung from the Finnieston Crane in Glasgow before being burned in Springburn in a Viking-style funeral, gaining international attention and The Paper Boat (1989-96) which sailed around the world from Glasgow to New York and back, making its way to the front page of the Wall Street Journal upon its arrival in New York in 1990.

Wylie was elected ARSA on the 21st of June 1989 and RSA on the 25th of February 2005.